In an attempt to address its critical labour shortage, the German government is developing its own version of a “green card,” the Chancenkarte (meaning “opportunity card”). For some time, industry organizations have been protesting, and the Labor Ministry has claimed that the gap is slowing economic growth.

The new “opportunity card,” announced in German media this week by Labor Minister Hubertus Heil, would allow foreign people to travel to Germany to look for work even if they do not have a job offer, as as long as they meet at least three of the following four criteria:

1) A bachelor’s degree or a professional qualification

2) At least three years of professional experience

3) Language proficiency or prior residency in Germany

4) Under the age of 35

The criteria are similar to those used in Canada’s points system, however the latter employs a more sophisticated weighting mechanism. In media interviews this week, the minister from the center-left Social Democrats (SPD) emphasised that there would be restrictions and constraints. According to him, the German government would restrict the number of cards issued each year based on labour market need.

Language and bureaucracy are the two most significant barriers to hiring qualified professionals in Germany.

“This is about qualified immigration, an unbureaucratic procedure, and that’s why it’s important to state that individuals with the opportunity card may make a livelihood while they’re here,” Heil told WDR public radio on Wednesday.

According to Sowmya Thyagarajan, there have been some advances. She moved to Hamburg from India in 2016 to get a Ph.D. in aviation engineering and is now the CEO of her own German firm, Foviatech, which develops software to improve transportation and healthcare services.

“I believe this points system might be a great chance for individuals coming from other countries to work here,” she told DW. “Especially given Germany’s dwindling youthful population,” Thyagarajan said, “her employer now offers precedence to Germans and EU citizens when hiring, simply owing to the procedural barriers involved for everyone else.”

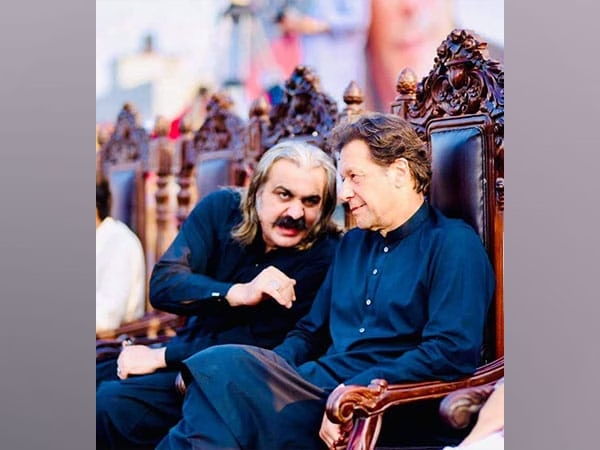

Hubertus Heil addressing the legislature

Labor Minister Hubertus Heil wants to increase skilled labour immigration.

New points, new challenges

Some people are unimpressed with Heil’s opportunity card. “It creates needlessly high barriers and complicates the system,” said Holger Bonin, research director at the Institute of Labor Economics (IZA) in Bonn.

According to Bonin, Heil’s points system will just need additional paperwork.

“Why don’t they make it more easier? Give them a visa to hunt for job, and if they don’t find anything within a particular time frame, they have to leave?” he said. “Adding new points merely complicates things — if these characteristics are relevant to companies, they can determine that during the recruiting process; they won’t require a card as a pre-selection.”

Indeed, according to Bonin, some of the qualities Heil mentions may not be that essential to German employers: for example, if they’re a multinational corporation that interacts largely in English, they won’t care whether candidates can speak German or have lived in Germany.

That is supported by Thyagarajan, who had various opinions on how effective the four criteria were: qualifications and language skills were both significant, she said, while age restrictions were less clear. “Age of less than 35, I’m not sure about that — you don’t have to be young, it really depends on how they’re truly competent,” Thyagarajan says, adding that in certain situations, a degree suffices: “For some job profiles, you don’t need experience, but for others, you do do have to be experienced.”

Germany has been dealing with a skilled labour shortage for some time. According to Gesamtmetall, the Federation of German Employers’ Associations in the Metal and Electrical Engineering Industries, two out of every five enterprises in their sector are experiencing production delays due to a shortage of personnel. According to the Central Association for Skilled Crafts in Germany (ZDH), the nation is lacking around 250,000 skilled artisans.

The number of skilled workers immigrating to Germany from non-EU countries has increased in recent years, although it remains relatively low. According to Mediendienst Integration, the number of skilled workers entering Germany in 2019 was slightly over 60,000, accounting for just 12% of total non-EU migration to Germany that year.

Germany has a few cultural disadvantages when compared to other Western countries seeking qualified workers: German is less widely spoken than English. “Skilled employees nearly usually hunt for opportunities in English-speaking nations,” Thyagarajan added. “It’s necessary (that our personnel know German) to some level since this is Germany, at least a working competency.”

Another difficulty is that German businesses place a larger value on credentials and qualifications, which are sometimes not recognised in Germany or take months to approve. “Introducing an opportunity card will not fix those difficulties,” Bonin stated.

Other structural issues for German businesses include Germany’s federal system, which means that various local authorities sometimes accept different credentials, and Germany’s dependence on paper bureaucracy, with workers sometimes requiring notary-approved translations of their certificates. This is another issue that Heil is seeking to address.

“I believe that, in addition to a contemporary immigration legislation, it is absolutely important to thin down the bureaucratic monster of recognising credentials,” he told WDR. To that aim, he would want to have a single agency that can promptly approve qualifications and back offices in Germany that can help overburdened consulates overseas.